Disrupted Continua

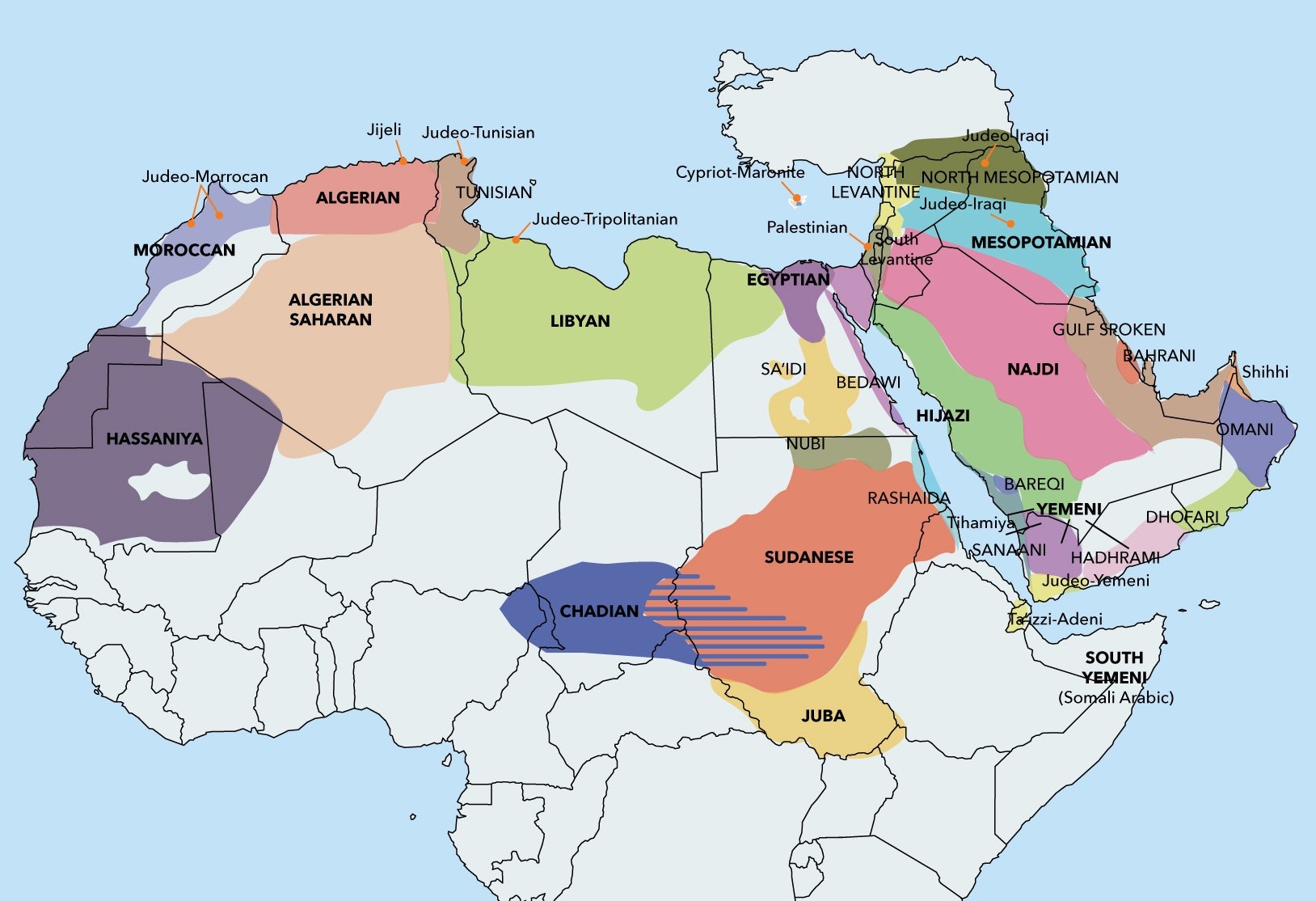

You live in Morocco and you speak Arabic. Everyone around you understands you perfectly. One day, for work, you need to go a bit east to Algeria, where they also speak Arabic. You’d expect everyone to understand you, but they say some words differently and use other words you don’t recognize. Duty beckons you further east to Egypt and now it seems like you can only catch half the words. To take a break from all that hard work, you go further east to Yemen. On landing at the airport, you find you simply cannot understand a thing.

You’re a bird in the arctic. You live in Norway, and one day you fly east to Sweden and see a very beautiful bird. The two of you spend a season raising a brood. “Hmm” you say. “I wonder if the birds are just more handsome as you go east. Let me see.” So you intrepid Norwegian pecker you, flap your way to Finland where you see a very beautiful bird and spend a season raising a brood. The next season you make your way over to meet your Russian soulmate and after a feather-y dust-up the two of you assume a brood is on the way. But it never comes. You see a Finn fly over and rush off with your Russian soulmate, and this season they raise a healthy brood together while you subsist on kasha and vodka.

A shiny axe sits in a museum. Its label reads “Abraham Lincoln’s axe”. The original axe was interred in his mausoleum of things in 1872. A few years later the handle began to rot and a diligent curator found the same forest from which the wood was drawn to replace it. In the early 1900s the blade began to wither and rust, so another diligent curator found a smithy that could replicate it exactly. The string that held axe to blade rotted away over the years and it too was replaced with utmost attention to detail. Today, can anyone see Lincoln’s axe?

These three examples highlight a really important part of education to me - we start with extremely rough categories. “Birds” - all birds are the same. “Arabic” - everyone who speaks Arabic understands each other. As we progress in our learning through a subject we realize that the earlier classifications were conveniences. Discrete taxonomies are easy to visualize and understand but they are a coarse filter on the underlying continuum of reality. We classify bison and cattle in different species, and for that matter in different genus(es?). Yet they can create viable offspring together. We create these taxonomies for our convenience, but assuming they are reality, rather than just one representation can be limiting.

We categorize all the Kurdish dialects together as one Kurdish language, but they are mostly unintelligible with each other. Meanwhile we categorize Serbian and Croatian as separate languages when in reality they are essentially the same language. As the inimitable Max Weinreich was quoted, bemoaning the state of Yiddish in Europe:

אַ שפּראַך איז אַ דיאַלעקט מיט אַן אַרמיי און פֿלאָט

Transliterated:

A shprakh iz a dialekt mit an armey un flot

Commonly rendered in English as “A language is a dialect with an army and navy”. If we take a moment to appreciate how intelligible this Yiddish sentence is with English, and another moment to see how “Hey hey Daloy politsey, daloy samoderzhaviye v’Rasey” is almost perfectly standard Russian (долой полицей, долой самодержавиев россии, Down with the police, down with autocracy in Russia), we can understand Weinreich’s point even more deeply. Yiddish at the time had no central authority to determine legitimacy or standard registers of the language. Or said another way - Yiddish was in continuum with German, Russian, Ukrainian, Polish, Hebrew and whatever other languages Yiddish people contacted on a daily basis. In turn-of-century Europe, it was largely militarized, centralized, secular states that standardized by detaching from neighboring languages. For the convenient administration of a state, army and a navy, one needs a common, distinct language - for shibboleth and harmony. In building it, you have to disrupt the continuity - between your language and the one next to it.

Whenever we try to simplify and communicate about the world we do so with disrupted continua. We try to speak of the center of clusters rather than the wide distribution of them. This is fundamental to statecraft (and maybe all cognition - reality is continuous but we have to process it in discrete moments), and highlighted in several examples in James C. Scott’s Seeing Like A State. Once you see reality as the state wants you to, the world is a lot less magical. Maybe once you see reality in any way that breaks continuum…the world becomes less magical. But that’s just the world innit.

I have a lot of thoughts about what a worldview that doesn’t disrupt continuum looks like. It doesn’t include learnings from a national-scale education system with a standard curriculum. It includes a lot more wonder and curiosity and delight at the surprises of nature.